Jaws at 50: How a Shark Changed Cinema

“You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

It’s been 50 years since those now-iconic words were spoken on the big screen. In July 1975, Jaws splashed into theaters and changed the face of summer movies forever. Half a century later, this Spielberg classic still sends chills down our spines—and continues to influence how we think about sharks, the ocean, and even prehistoric marine life.

Why Jaws Is One of the Most Iconic Films in Movie History

In a world full of blockbuster franchises and cinematic universes, one film still stands at the top of the food chain—Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. Released in 1975, Jaws didn’t just break records—it redefined modern cinema. But what exactly made this shark thriller the most well-known movie in the industry?

It Invented the Summer Blockbuster

Before Jaws, the summer movie season was a quiet time for studios. That all changed when Universal released the film in June 1975 with a wide national rollout—an unusual tactic at the time. Thanks to massive TV marketing, terrifying trailers, and strong word-of-mouth, Jaws exploded at the box office. It became the first film to ever gross over $100 million, setting the standard for what we now call a "blockbuster."

Suspense Over Spectacle

Ironically, the film's most famous attribute—the shark—was rarely shown on screen. Due to the constant mechanical failures of the animatronic shark "Bruce," Spielberg was forced to rely on creative filmmaking techniques to build suspense. He used haunting music, underwater POV shots, and strategic editing to suggest the shark's presence instead of showing it outright.

This made the fear psychological, not just visual—and it worked. Audiences were terrified not because they saw the shark, but because they didn’t.

That Score

Two notes. E and F. That’s all composer John Williams needed to terrify an entire generation. The Jaws theme is now one of the most recognizable pieces of music in film history. It’s simple, primal, and incredibly effective—mirroring the lurking danger of an unseen predator.

It Changed Public Perception of Sharks

While the film unintentionally sparked decades of fear and misunderstanding about sharks, it also had very real consequences for how the public viewed these animals. Many viewers developed a deep fear of the ocean, with some even refusing to swim in the sea after watching Jaws.

Others were inspired not by curiosity, but by conquest—heading out to hunt and kill sharks as trophies, emulating the film’s character Quint. Shark populations suffered as a result, with sport-fishing tournaments and thrill-seeking hunts on the rise.

Yet, at the same time, Jaws ignited a widespread fascination with marine life. People who once feared the deep began learning about real sharks, ancient species, and the complex ecosystems that sharks help sustain. The movie stirred both fear and fascination—two powerful forces that shaped public interest in ocean life for decades to come.

This cultural impact is still felt today in the fossil world. Many fossil collectors—including those fascinated by Megalodon teeth—cite Jaws as their first introduction to marine predators.

A Legacy That Still Bites

Even after 50 years, Jaws continues to influence everything from horror movies to ocean documentaries. It earned three Academy Awards, launched Spielberg's legendary career, and inspired generations of filmmakers, scientists, and fossil hunters alike.

In many ways, Jaws is more than just a movie—it's a cultural landmark. It made us fear the water, respect the ocean, and marvel at the natural world, both past and present.

Behind the Scenes of Jaws: Engineering a Legend

Joe Alves, the production designer for Jaws, created three different mechanical sharks for Spielberg to choose from: an 18 ft shark, a 26 ft shark, and a 32 ft shark. Spielberg felt the 18 ft version wasn’t intimidating enough, but the 32 ft shark looked too unrealistic. So, they went with the 26 ft version — a perfectly terrifying middle ground, (and just about the size of a Megalodon shark. Would you like to own a real Megalodon tooth? Some say CHUM10 might help you get your hands on one… ) Spielberg selected it as the star of the show, affectionately (and ironically) naming it “Bruce” after his lawyer.

However, Bruce would quickly earn a different reputation on set.

Although the name "Bruce" was initially a tongue-in-cheek nod to Spielberg’s legal counsel, it stuck with the cast and crew for a different reason: the mechanical shark constantly malfunctioned. Not designed to operate in the unpredictable saltwater conditions off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, Bruce was plagued by hydraulic and buoyancy issues. The salt corroded its internal components, and frequent exposure to ocean swells made filming extremely difficult.

Spielberg’s decision to shoot Jaws on location rather than in the controlled environment of a studio tank only magnified these challenges. He insisted on the realism of open ocean filming to immerse the audience in the terror, but the result was a logistical nightmare. Harsh winds, rough seas, and frequent equipment failures led to massive production delays. What was originally scheduled as a 55-day shoot ballooned into 159 days, running more than 100 days over schedule and significantly over budget.

Yet, these very setbacks helped shape the brilliance of the final film. With Bruce frequently out of commission, Spielberg was forced to imply the shark’s presence rather than show it—giving rise to the film’s most suspenseful scenes and proving that what you don’t see can be far more terrifying than what you do.

Where is "Bruce" today?

If you’re ever in Los Angeles, make a stop at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures—because that’s where Bruce, the legendary shark from Jaws, now calls home. Suspended from the ceiling near the elevator, this massive animatronic weighs in at 1,208 pounds and is an impressive sight to behold.

But here’s the catch: this isn’t the exact shark used in the 1975 film. Known as Bruce IV, this version was created using the original mold from the movie. For 15 years, he greeted visitors at Universal Studios Hollywood before eventually being moved to a junkyard in Sun Valley, California.

There, he sat for 25 years—sunbaked, weathered, and nearly forgotten. Then in 2016, junkyard owner Nathan Adlan generously donated Bruce IV to the museum. His authenticity had been confirmed back in 2010 by Jaws special effects supervisor Roy Arbogast.

Decades in the California sun had left Bruce in rough shape, but a dedicated restoration team brought him back to life. It took seven months of careful work to return Bruce to his former glory—ready once again to terrify and fascinate, just as he did on the big screen.

The Truth Behind the Jaws Poster Shark: Not a Great White?

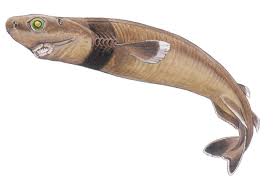

While Jaws turned the great white shark into a pop culture icon, the menacing predator featured on the film’s legendary poster wasn’t actually a great white at all. Instead, it was based on a shortfin mako shark. The image of the shark rising vertically with its mouth wide open—on a collision course with a lone swimmer—was inspired by a taxidermied mako that still exists today. That shark is preserved and on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Poster artist Roger Kastel used a reference photo of the mounted mako shark to create the now-famous artwork. He exaggerated certain features, like the teeth and body size, to make it feel more menacing and monstrous, perfectly matching the tone of Spielberg’s thriller. Interestingly, mako sharks and great whites are related—they’re both part of the Lamnidae family—but makos are typically smaller, faster, and sleeker in appearance. Short-fin makos are actually among the fastest sharks in the ocean, capable of reaching speeds over 40 mph.

The original painting for the poster was a striking piece, but it mysteriously disappeared in the early 1980s and has never been recovered. Only reproductions exist today. As for the swimmer in the image? She wasn’t based on a real person—Kastel added her for dramatic effect, creating one of the most chilling and recognizable movie posters in cinematic history.

So while Bruce the animatronic shark from the movie was modeled after a great white, the poster that helped sell the terror to audiences was built on the back of a mako shark—proving once again that Hollywood magic often starts with something real.